On German Military Brothels and Voluntariness

year: 2016, author: Anne S. Respondek / translator: Mario Respondek

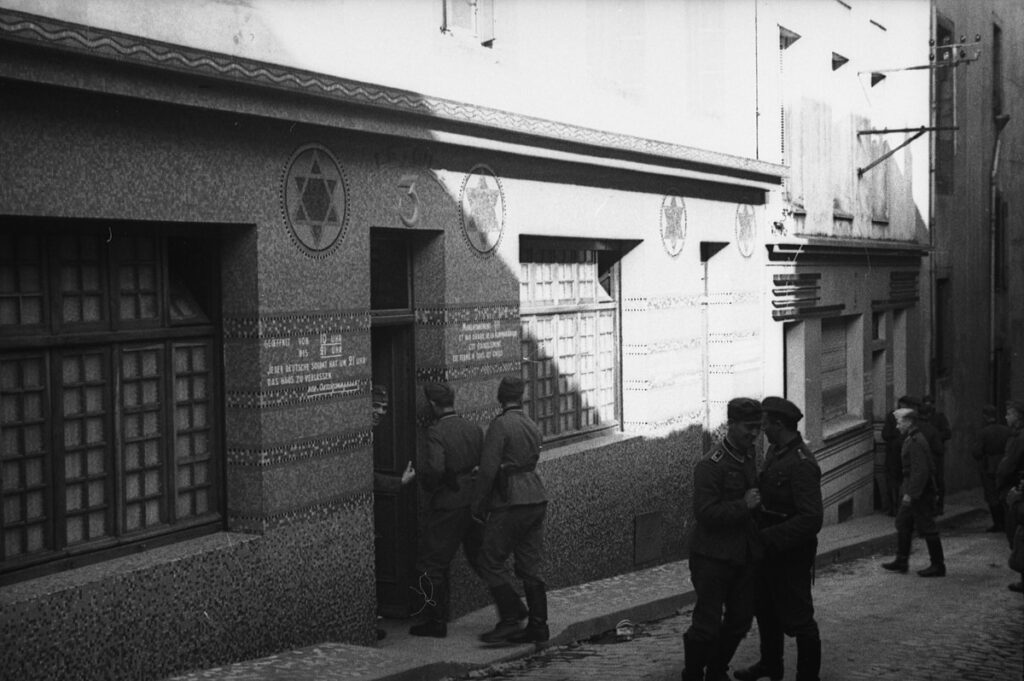

(photo: German MIlitary Brothel in Brest in a former jewish house, 1940. source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 101II-MW-1019-07 / Dietrich / CC-BY-SA 3.0)

War and sexualised violence, including forced prostitution of women, unalterably go together within patriarchal systems.[1] This has been known even before the crimes committed against women and girls who were forced into prostitution in Japanese military brothels during WW2 were accounted for.[2]

Brothels for soldiers are no Japanese creation in particular. The Great War, too, has given rise to German brothels at base that were erected by the state, but also mobile field brothels similar to caravans, and brothels in barracks behind the front line.[3] From 1941 onwards, the National Socialist state tied in with this tradition and transformed into a pimp by erecting brothels galore in almost all occupied countries. These were opened not only for male inmates of concentration camps[4], foreign workers and forced workers[5], or the Ukrainian guards of concentration camps, but also members of the SS[6], members of the Waffen-SS and police[7], foreign military units, foreign volunteers in the army groups[8], for the Todt Organisation, the NSKK and the Wehrmacht (i.e. German navy, ariforce, army) – always differentiated between brothels for officers, for corporals, for soldiers, for members of non-German nationality in the Waffen-SS, respectively members of Eastern peoples battalions, for the merchant navy, and for members of the German State Railways.[9]

The state of research regarding these brothels is not very diverse. They constitute a taboo topic, similar to that of concentration camp brothels; the myth of voluntary registration into them deconstructed only in 2006 by Robert Sommer.[10]

In order to settle the issue about voluntariness, I have analysed an individual case to shed some light on the mechanisms that preceded „taking up residence“ in a brothel. The analysed source is a criminal investigation file on a Polish saleswoman from Poznan (known as Posen at the time) who was taken to a Wehrmacht brothel. The document annotates that she registered voluntarily. If this is really so, and if this committer statement – for this annotation was made by the criminal investigation department – can be acknowledged directly and uncritically, will be the main subject of this essay. An additional prospect will be an in-depth examination of the Wehrmacht brothel system.

The criminal investigation file labelled Gewerbsunzucht Maria K. (Prostitution Maria K.) in the care of the National Archive Poznan contains 47 pages covering the years 1940 to 1943. It was issued by the national criminal police department (Kriminalpolizeileitstelle Posen). Up to this point, this file has not been thoroughly analysed and interpreted, though it has been mentioned in the film Frauen als Beute – Wehrmacht und Prostitution[11]. The research literature has to date failed to produce texts that dissect singular case files which show persecution history. The pages in this file are made up of records from the health authorities, criminal investigation department, and secret state police, reports given by the military patrollers that apprehended Maria K., as well as further reports the criminal investigation department made on her personality.

According to the first page of the case file, Maria K. was born the illegitimate child to a dressmaker 1919-10-26 in Rogasen (now Rogoźno in the Oborniki district, Poland). She left the Polish public school upon completion of 6th grade and took up work as a salesclerk in a general store specialised in food items from overseas, then moved to Posen, where she worked at a café. She was a Roman Catholic and fluent in German an Polish. The German authorities noticed her when she turned 21. The first document in the case file has three photographs attached to it, showing a neatly-dressed young woman, and describes her appeareance. It makes Maria out as a woman of 5ft 2, slim, with long medium-blonde hair and gray-blue eyes. The description furthermore mentions her tooth gap, earlobe piercings, and freckles.

The case file argues that the following incidents have taken place in the period 1940-43: It accuses Maria of having sexual intercourse with a citizen of the German Reich and suffering from a venereal disease. It is probable that Maria was denounced to the criminal police by a person from her inner circle. The records say that – once a forced medical check had borne no evidence of a venereal disease – she disputed taking money in exchange for having sex with the man. However, gifts and loans are interpreted by the investigating person as „a harlot’s wage“ (Hurenlohn). The accusations against her furthermore claim that her ID, identifying her as German instead of Polish, was a fake. Maria K. confessed that this was true and consequently received a six week sentence for forgery of documents. At this point, the secret state police stepped in, arrested Maria, interviewed her regarding her relationship with the German citizen and gave instructions that she be assigned to a Wehrmacht brothel. While Maria served her sentence, several German soldiers claimed that she had infected them with a venereal disease (although none could be found in her).

On a walk with a German soldier, Maria was apprehended once more by patrollers, arrested, and interviewed by the secret state police. After her incarceration at a makeshift camp (Fort 7), the secret state police again instructed the criminal police to assign Maria K. to a brothel. She was then given a Merkblatt für Prostituierte (instruction sheet for prostitutes), informing her that she was to follow these instructions, or would be taken to a concentration camp otherwise. Her signature on this instruction sheet furthermore bound her to live at the brothel 19 Fischerei St. in Posen, to subject herself to the authorities, to observe the rules and agree to undergo obligatory medical checks.

Her life following the imprisonment at the brothel was marked by a number of incidents. After a day pass from which Maria K. admittedly returned intoxicated, she was reported to have discommodated German citizens (Reichsbürger) and to have made insulting retorts which lead to a criminal complaint against her. After a short leave aimed to „reinstate her health“ she got herself involved in a police matter yet again in another event: Reportedly, Maria K. rampaged in the brothel while drunk and bit a medical orderly in the process, before making an escape from the brothel. When she did not show up for her medical check, the local health authorities reported her to the criminal police department. After a few days, she turned herself in – for fear, as she later admitted – and was taken to a hospital, then brought before a judge. Once again, the secret state police intervened and, without further ado, branded the former salesclerk as a previously convicted prostitute without permanent residence, as a tramp who prostitutes herself even outside the brothel and presents a source of infection. In other words, she was stigmatised for being precisely the product of what the government agencies themselves had renderred Maria K. to be. The criminal police confirmed that Maria K. and an officer who had been denied access to the brothel had met up at a local establishment. Maria K. denied this and instead maintained that the man was following her until she removed herself from the situation. She explained that she had been listening too much to the talk of the other girls who kept bringing up concentration camps, and that the administrator of the brothel had threatened to transfer her to one. She stated to have lost her nerve because of this and fled the brothel out of fear. In January 1942, Maria K. was taken to court for missing an obligatory medical check. She was sentenced to serve one year at a prison camp.

However, after serving her sentence, she was not released. Instead, she was kept in preventive custody. The resulting presentiment had her write a letter asking to be allowed to work again, for she would be willing to work, even return to the brothel. Her promises to improve put into writing did not help. The criminal police department put together a criminal CV concerning the by then homeless, jobless, previously convicted prostitute. The document has her classified as an antisocial element who ought to be detained ‚in the interest of the German national character and people’s health‘ (Volkstumspflege und Volksgesundheit). It also denies any chance for improvement and condemns her request to transfer from preventive custody to a brothel. Her fear and her instinct of self-preservation were thus misconstrued as an affront. On March 4th 1943, Maria K. became an inmate at Auschwitz.

With the inclusion of contemporary documents, a series of conclusions and theses can be drawn from interpreting of this case file:

There are several entities that were involved in Maria K’s placement at a brothel, as well as keeping her there. Once she had been noticed, she was completely under the state’s control. The state interfered with Maria’s life in the form of the criminal police department, the secret state police, the public health authorities, the Wehrmacht for which the brothel was established, as well as military patrollers and medical orderlies. The discriminating mechanisms inherent in this example are threefold: sexism, classism, and racism.

As a woman, Maria was monitored and controlled, because as a prostitute she was of value to the male Wehrmacht, who were supposed to keep up morale[12] through one-sidedly enjoyable encounters. That way, they were allegedly not as likely to hunt down ‚women as spoils of war‘ and could be certain not to catch venereal diseases seeing as the women in the Wehrmacht brothels were under constant supervision of the health authorities, staff surgeons, and paramedics[13]. If the women failed to show up for a medical exam at the public health department, the latter would report this to the criminal police department, which would give cause for the women to be arrested[14]. Women who broke the rules of conduct at a brothel were threatened to be transferred to a concentration camp[15].

The use of condoms was obligatory,[16] though it was the women who were to see that this rule be followed. This was problematic. Numerous times, the armed punters asserted their claim to have sex with the prostituted women without a condom in the privacy of their rooms[17]. As a consequence, these women were exposed to infections, which led to their confinement in hospitals that had been transformed into detention centers[18]. Some punters also claimed to have been infected by a registered prostitute to avoid punishment for sexual relationships with local women in the occupied areas, or to cover up rape or visits to unregistered prostitutes, as this was forbidden[19].

Maria K. was denounced several times by members of the armed forces, forced to undergo medical checks because of this, and taken into custody[20]. However, as made clear above, a venereal disease was never detected in her, neither during any of the forced stays at a hospital[21] nor her medical checks. Notably, in all documents of the Wehrmacht and in the case file at hand, too, the term „Ansteckungsquelle“ (source of infection) consensually bears a female connotation[22]. That it was male punters, too, who infected the women, is never mentioned. Handouts bearing instructions on sanitary measures even went as far as to victimise punters, saying they were victims of female sources of infection, victims of their own needs[23], victims who would relent to adultery in „moments of weakness“[24].

A soldier suffering from venereal disease was not considered fit for action and caused worry because he might not be able to beget healthy children later[25]. While the soldiers were instructed to see themselves sanitised after a visit to a brothel, reports indicate that the penalties for evasion of sanitation[26] were basically not being acted out until 1943[27]. Thus, the women, including Maria, were permanently exposed to sanitary hazards in the brothels. Furthermore, there are reports of excesses, sexual assaults, groups of drunk soldiers who entered brothels by force, and physical violence against the women[28].

Von Brauchitsch explained that the establishment of military brothels was supposed to minimise the expansion of homosexual activities and prevent rape[29], but this was not the case[30]. Quite the contrary, in fact, because the few soldiers that were actually taken to court for rape in the occupied regions thus claimed to have mistaken the corresponding victim for a prostitute at the time[31]. In the end, even the leadership of the Wehrmacht had to admit that, for one thing, prostitution does not only fail to grant sexual gratification („Triebableitung“) and containment but effects an increase in demand for even more prostitution, and for another thing, that it bestialises soldiers sexually in a way that makes them extend their misogynic perception of women not only to women outside prostitution in the occupied countries, but also „their“ women at home[32].

The discrimination against Maria on the basis of social class similarly rests on priciples of distortion. As a prostitute, whom the criminal police took her for, and whom she ultimately became in the brothel, she was categorised as „asozial“ in the eyes of the authorities. As long as the state was able to make use of her, however, it did exactly that. As a „dishonoured“ woman and „asocial“ character, Maria could still be made use of as a prostitute, for as long as she would not resist. It was not before she bit a medical orderly, displayed resistance, and ultimately ran away, that the criminal police put into writing that she was to be taken to a concentration camp in accordance with the law. The very moment „asocial“ Maria K. refused to help with the German soldiers‘ „Geschlechtsnot,[33]“ she was of no more use to the authorities. The state turned Maria from a salesclerk with a job and permanent residence into a forcefully brothel-based prostitute, then went on to accuse her of just that. However, her undoing in a concentration camp on the grounds of her „asocial“ status was planned only after she fled. From that point on, the state considered her to be a renitent, irredeemable, homeless and unemployed prostitute, who is no longer of use to the „Volksgemeinschaft“[34] and who has shown no improvement in character even after several sentences of detention.[35]

Nothing indicates free will in Maria’s transfer to a brothel. The criminal police cancelled the words „zwangsweise untergebracht“ (forcefully placed) and replaced them with „eingewiesen“ (transferred) in her case file. It is obvious that she did not volunteer for „duty at the brothel“ („Bordelldienst“), clearly not after the numerous times she was apprehended and pressured by the secret state police.

Maria was threatened with concentration camp, and she was incarcerated. She was forbidden to leave the brothel at night on police orders. However, during the day, she was not allowed to be seen in public streets and places, as pointed out by the instruction sheet given to her. Leaving the brothel at all, even if just for a stroll, required official permission by the authorities. A leave of absence had to be officially sanctioned as well, and was not always granted. While in the brothel, she was not free to decide to lay down her prostitution, not even temporarily. Leaving the brothel would mean to be denounced by patrollers, police, soldierly punters, and civilians who felt „bothered“ by her presence, so that she would be apprehended again and taken to the brothel. After several rearrests, interviews by the secret state police and criminal police, after one year in a punishment camp, she got a social prognosis by the authorities that – for the first time – claimed that her registration into the brothel was a matter of her own free will. It was only then, that Maria, who seemingly suspected a transfer into a concentration camp, positively begged to be taken back to the brothel. For she would be „willing to work.“ Regardless, the criminal police maintained a rigorous course. They listed all her „transgressions“ along with distorted facts and gross exaggerations, as formerly described. They went even further and imputed her with a rebellious predisposition, and a renitent character immune to educational and disciplinary measures. This unfavourable social prognosis lead to the recommendation that she be taken to a concentration camp. A handwritten sidenote remarks on her voluntary decision to return to the brothel. Notwithstanding, how voluntary can decision made in fear for one’s life be, really?

Maria was a victim of racial discrimination, too. Being Polish in a protectorate area, she was a member of the German Reich, but she did not have the status of a citizen: She was not to enter German establishments (a rule she disregarded), she was to keep curfews, and she was regarded to be of „inferior race“[36]. Among other things, she was arrested for „Rassenschande“ (racial defilement) and „verbotener Umgang“ (forbidden contact)[37]. A decree from the Reich governer, however, established that Polish women who have sexual relationships with citizens of the German Reich were to be taken to a brothel[38], where they would be forced to turn this very same „Rassenschande“ into practice. The contradictory nature of this conjuncture was resolved by Heinrich Himmer, and the senior medical officers forwarded this to the troups:

The girls were Polish. Sex with Polish women in the brothels would not be considered a social act, since for the Polish this is under prohibition by the Führer’s decree. The connections between the harlots and their various visitors are of a functional and economical nature. They also do not have the social impact that an acquaintance made in the publicness of urban space, or street prostitution, or any other kind of getting acquainted would have. A social act requires a certain amount of respect and rapport that the brothels do not facilitate.[39]

Outside of the brothel, however, Maria was forbidden from contact with „Reichsdeutschen.“ She was arrested several times for speaking with German soldiers outside the brothel, or because they accompanied her to the tram.

The Wehrmacht was concerned about soldiers losing the enemy image they held towards the Polish, if they had free relationships with Polish women, or that they could be spied on, which was feared especially in the Soviet Union.[40] The mass processing in the brothels, however, would leave no time to recognise the women as human beings.[41] What is more is that this did not just davalorise the women themselves, but it was also a statement from German to Polish men that devalorised the Polish nation.[42]

Punters also played a bigger roll in the abuse-system of Wehrmacht brothels. They chatted up Maria in the streets, for which she was then punished, they followed her, harassed her and denounced her. They caused her to be arrested several times. In the brothel itself, they used her, humiliated her and acted out other forms of abuse. Where this behaviour stems from can be drawn from interception reports, which make clear how the soldiers perceived women in general, and women from the occupied countries in particular.[43] The interception reports also significantly illustrate how rape, execution, displacement into brothels &c. were considered normal[44], if not even necessary, or entertaining. To them, women were mostly fair game and sex objects, consumer goods, to which every soldier is entitled to: like good wine, good food, good music, and pretty women – voluntarily, or, if not possible, involuntarily.[45]

What is very clear, is that the Wehrmacht soldiers knew, or at least were in a position to know, that the women were not there on their own account, but they did not care either way.[46] To the contrary, the prostituted women were even partially blamed.[47] Women were talked about with shocking indifference, as illustrated by an example from an interception report:

In Wasaw, our troops cued up at the front door. In Radom, the first room was full, while our truck drivers were waiting outside. Each woman had 14 to 15 men in an hour. They replaced the women there every other day there.[48]

What it meant to be „replaced,“ is a matter of conjecture. These women were seen as commodity. A situation report constistutes:

The „quality“ of the girls is constantly monitored and heed is paid to only engage young, presentable and pretty girls, as this seems to be the only way to compete efficiently with uncontrolled prostitution.[49]

Soldiers saw rape and prostitution as an offense against the honour of a woman. Seeing how, to them, women in the occupied countries did not have any honour, however, they had a lower inhibition level to be physically abusive toward them.[50] The soldiers‘ boasting – including narratives of abuse and rape – among the troups substantiates the impression that soldiers understood their actions as „sexual adventures“ and as a means to prove their manliness.[51] After a fashion, this turns a community born of necessity into a community of abusers, thereby mirroring in War their civil society’s sexist-classicist-racist worldview without restraint.[52]

It can be stated that the soldiers willingly used the latitude they were handed. Visiting a brothel was a man’s personal choice. With every visit to a brothel, the soldiers chose to exploit a scope of power that was facilitated by the state and promised them priviledges, namely the abuse of female bodies. Not only were the soldiers aware of the coercion the women were exposed to, and readily benefitted from it. They also implemented this coercion themselves. As members of a community of abusers and accomplices with the NS state as their patron, they benefitted from the system of Wehrmacht brothels, and used it, and consequently supported it.

Since the abuse manifested in their private actions when they chose to excert it, the soldiers‘ choice to fill out the scope of power they were granted by the state adds to their deeds a political dimension.[53]

Maria’s point of view never made it into the case file, of course. It can be reconstructed, at most. From the point that she was taken to the brothel, a good many mentionings of Maria in connection with alcohol can be found in the file, as well as accounts of her physically defending herself and fleeing. What it all amounts to is this: Maria was held captive again and again, and she did not even have a say in the price set to have sex with her[54], which left her deprived of any right of decision. She was subjected to so many regulations that she was virtually forbidden from ever leaving the brothel without the threat of being arrested looming over her. This was aggravated by very real fears of being taken to a concentration camp, a pentalty camp, or more interrogations.

From France we know of physical abuse by punters, shootings taking place in brothels, punters imposing sex without condoms, and women facing imprisonment for disciplinary reasons when they defended themselves against abusive punters[55]. Further living conditions Maria faced in the brothel are the high number of punters in the troup brothel and the educated guess that she might not have been allowed to turn away any punters either. Furthermore, there are reports that inform us about insanitary conditions in the brothels, where sometimes soap and charcoal needed for water conditioning were scarce[56]. Assessed in quality and assigned a number by the authorities, Maria was treated like an object, used to fit out the Wehrmacht brothel. All of these things are massive attacks against Maria’s human dignity, and also her self-determination.

The case of Maria K. adduces how a „voluntary registration“ into a Wehrmacht brothel was constructed in spite of a great many contrary facts, every single one of them indicative of forced prostitution in their own right: arrest, persecution, pressure put on her by the Gestapo who made it unmistakeably clear that they wanted to see Maria in a brothel, the fact that Maria was not allowed to terminate the arrangement at the brothel on her own will or without permission by the authorities, as well as the truth that she was held prisoner, threatened with penalties, and could not put an end to her prosititution on her own account, and eventually the extorted request she made while in custody and threatened to be taken to a concentration camp.

The modus operandi by which Maria K. was lead into the brothel is not unique. On the contrary, the mechanisms in place that had her taken to a military brothel are similar to those in France. In fact, the majority of requests to join a brothel were products of extortion[57], and what occured at the brothels was ultimately forced prostitution, seeing as the women could not that easily quit their ‚employment‘. Since the circumstances in Warthegau resemble those in France, which has been a subject of research before, and because in this case examination it has become evident that it involved forced prostitution, it should be abundantly clear why labelling the women’s activities at the Wehrmacht military brothels as ‚voluntary prostitution‘ is obsolete – as is denying the underlying forced prostitution and sexualised violence.

The research situation is sparse. It is true that the subject gets touched on here and there[58]. The only works based on an examination of primary sources and therefore leading to truly new conclusions, however, are those by Franz Seidler[59], Insa Meinen[60], Max Plassman[61], and Wendy Jo Gertjejanssen, who wrote on sexualised violence at the eastern front during the second world war[62]. The scarce research literature in existence seems to bear witness to the troubles connected to the contextualisation of prostitution in Wehrmacht military brothels and sexualised violence against women during the war. What is more is that many times the women get devalualised in the process, and the events are played down.

The definition of „Zwangsprostitution“ (forced prostitution) within German research literature is intollerable, and so is the understanding of „nicht ganz freiwillige prostitution“ (not entirely voluntary prostitution) as forced labour rather than serial rape[63].

It seems strange that even acknowledged compulsion does not result in a contextualisation of Wehrmacht military brothels with sexualised violence against women at times of war[64].

It is also strange how violence against the women in question gets played down[65], how clauses imposing compulsory residence on them (Zwangsaufenthaltsklauseln) get equated with normal working conditions and how constructed voluntary registrations get unreflectively accepted[66], how there can be solicitations to sympathise with the perpatrators who could not get hold of enough women as a kind of spoils of war[67], how there can be claims that a high fluctuation were indicative of the Wehrmacht not having to use force[68], how someone can remark that the reprisals concerned both sides equally and conclude that the women also enjoyed protection (from fraud by Johns, from STDs) while claiming that the establishment of the brothels were beneficial to the fight against STDs in the army as well as to an increase in combat power[69], and last but not least how one can make obserations so remote from everyday life such as the statement that the people running the brothels having an interest in it being profitable were a sign of the absence of force being used against the women[70]. When compared to modern conditions, „arguments“ like this reveal their absurdity at any rate, as well as an ignorance with regard to the mileu, misogyny to some extent, and a lack of cerebration concerning the prostitution system and how it fits into a certain social order. Drawing this sort of conclusions seems bewildering and strange.

It can be seen clearly that mass forced prostitution existed, and it remains unclear why this sort of forced sexual contact does not get to be acknowledged as a form of sexualised violence against women at times of war[71]. The formerly affected countries will be just as perplexed by German history reappraisal culture giving this kind of picture. In modern Germany, a country that has changed into Europe’s human trade centre no. 1 since the 2002 prostitution law was passed[72], that kind of reappraisal is bound to be coloured by the regional social climate and a rampant punter culture. However, this does not make it right, not even close. What would be the right thing to do in an examination of whether forced prostitution was in place, is to ask this:

Is a woman demanded to enter prostitution by means of pressure, force, violent threats, external control, arrest, or massive interference with, and assault on life and limb? Is a woman being kept in prostitution by means of pressure, force, arrest, deprivation of liberty, violence, or at the threat of punishment? Is she free to stop being prostituted at any time and at her own request without having to fear negative effects (persecution, arrest, legal punishment, violence)? Is she free to turn down punters? Can she decide on prices and practices herself? Is she free to defend herself when assaulted by punters? Are there restrictions to her freedom of movement? Is there some sort of confinement?[73]

It should be clear to see for everyone what Maria K. actually got caught up in.

Playing down these women’s experiences should be avoided. What is much more necessary, is reflecting upon the system of violence that prostitution constitutes in a patriarchial society in general. What is also necessary is raising an awareness for the mechanisms and traditions of the mileu that overcomes sympathising with punters and pimps and the people running the brothels (no matter if they happen to be soldierly German occupants).

Having said that certain aspects and views have not yet been examined, the same can be said with regard to entire regions. A small number of clues indicates that the more east the brothels were erected, the more unsubtle the bureaucratic pressure got, and all the less attention was paid to disguising violence against women by the authorities: East of the Warthegau women seem to have been taken to the brothels through displacement and kidnappings (including large numbers of girls who had never had sexual contact before), women seem to have been selected out of cues in front of employment offices, and very often women seem to have been shot dead after an infection with STDs[74]. Women from Ravensbrück were also selected for the Wehrmacht brothels. An analysis of the in part only recently accessable documents from Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia and other eastern European countries is still pending. One can only hope that they will be analysed with a trained eye, so that the women will not be ridiculed by subjecting them once again to objectification or by denying the violence done to them.

(c) Anne S. Respondek

Literature

Akte „Maria K.“. Staatliche Kriminalpolizei, Kriminalpolizeileitstelle Posen. Gewerbsunzucht. Staatsarchiv Poznan, Sign. PL 53/1024/18. |

Amesberger, Helga, Auer, Katrin, Halbmayr, Brigitte, Sexualisierte Gewalt. Weibliche Erfahrungen in NS-Konzentrationslagern, Wien 2010.

Ayaß, Wolfgang, „Asoziale im Nationalsozialismus“, Stuttgart 1995.

Bartjes, Heinz, Das Militär – Sondertfall oder Fortsetzung männlicher Sozialisation, in: Evangelische Akademie Baden (ed.), „Vergewaltigung. Militär und sexuelle Gewalt – Ursachen und Folgen in Kriegs- und Friedenszeiten, Baden 1994, p. 19-37.

Beck, Birgit, Wehrmacht und sexuelle Gewalt. Sexualverbrechen vor deutschen Militärgerichten 1939 – 1945, Paderborn 2004.

Clauß, Ludwig Ferdinand, Rasse und Seele. Eine Einführung in den Sinn der leiblichen Gestalt, Berlin 1939.

Corbin, Alain, Wunde Sinne. Über die Begierde, den Schrecken und die Ordnung der Zeit im 19. Jahrhundert, Stuttgart 1993.

Der Heeresarzt im Oberkommando des Heeres, GenStdH/Genu, Az. 1271

(Ila), Nr. I/13017/42, HQuOKH, den 20. März 1942, Bezug: Verfügung

OKH/GenStdH/GenQu/Az.: 1271 IV b (Ila) Nr. I/1 3016/42 vom 20.3.1942, Betr.: Prostitution.

Der Heeresarzt im Oberkommando des Heeres, Gen St d H/Gen Qu Az. 265 Nr. 17150=4o, Abschrift. Betr.: Prostitution und Bordellwesen im besetzten Gebiet Frankreichs, H Qu OKH, den 16.7.1940, Bundesarchiv/Militärarchiv RH12-23-1371.

Der Oberbefehlshaber der 15. Armee, A.H.Qu., den 12.7.41, Betr.: Bekämpfung der Geschlechtskrankheiten, Abschrift, Bundesarchiv/Militärarchiv RH20-15-156.

Der Oberbefehlshaber des Heeres, Nr. 8840/41 PA2 (I/la) Az. 15, H Qu OKH den 6. September 1941, Geheim. Betr.; Selbstzucht, Bundesarchiv/Militärarchiv RH12-23-1371.

Der Oberbefehishaber des Heeres, Nr. 8840/41 PA2 (I/la) Az 15, H Qu OKH den 6. September 1941, Geheim. Betr.: Selbstzucht, Anlage 1 Nr. 18497/40, 31. Juli 1940, Bundesarchiv/Militärarchiv RH12-23-1371.

Der Reichsminister des Innern, lV g 3437/39 5670, Berlin vom 18. September 1939, Betrifft: Bekämpfung der Geschlechtskrankheiten, Bundesarchiv/Militärarchiv RH12-23-1818.

„Der Sanitätssoldat“. Abschnitt über die Schutzbehandlung. p. 35, Bundesarchiv/Militärarchiv RH12-23-994.

Div.-Arzt 162.Inf.Div., o.U., den 12.3.43, Betr.: Bordelle auf dem Truppenübungsplatz Neuhammer. Bezug: Ferngespräch des stellv. Wehrkreisarztes VIII mit dem Adjutanten des Div.-Arztes am 11.3.43 An den Korpsarzt beim stellv.Gen.Kdo. VIII A.K. (Wehrkreisarzt VIII) Breslau. Bundesarchiv/Militärarchiv, RH 26-162-58.

Drolshagen, Ebba, Der freundliche Feind. Wehrmachtssoldaten im besetzten Europa, München 2009.

Drolshagen, Ebba, Nicht ungeschoren davonkommen. Das Schicksal der Frauen in den besetzten Ländern, die Wehrmachtssoldaten liebten, Hamburg 1998.

Eckart, Wolfgang und Plassmann, Max. Verwaltete Sexualität. Geschlechtskrankheiten und Krieg, in: Melissa Larner, James Peto, Colleen M. Schmitz (eds.) für das Deutsche Hygiene-Museum und die Welcome Collection, Krieg und Medizin, Dresden 2009, p. 100 – 117.

Eigendorf, Jörg u.a., „Deutschland ist Umschlagplatz von Frauen geworden“, vom 3.11.2013, URL: http:/www.welt.de/politik/deutschland/article121490345/Deutschland-ist-Umschlagplatz-fuer-

Frauen-geworden.html (last checked July 19th 2015).

Feldkommandantur 581, Verwaltungsstab, Vw.Gr. I/2 an die Kreiskommandanturen Rennes, St.-Malo, Fougéres, Redon, Betr.: Überwachung der Prostitution – here: polizeiliche Massnahmen und Strafen, Rennes, 4. April 1941, Bundesarchiv/Militärarchiv RH36-444.

Formular für die Kontrolle der Hygieniker im Generalgouvernement. Berichtformular. Bundesarchiv/Militärarchiv RH12-23-1818.

Frauen als Beute – Wehrmacht und Prostitution. (Title of the English edition: „Women as Booty“) Redaktion: Beate Schlanstein, Regie: Thomas Gaevert, Martin Hilbert, Produktion: Aquino Film, WDR. Deutschland 2005, Erstausstrahlung ARD 12.01.2005).

Gertjejanssen, Wendy Jo, Victims, Heroes, Survivors. Sexual violence on the eastern front during World War II, Ph.D., University of Minnesota, 2004.

Hirschfeld, Magnus und Gaspr, Andreas (ed.) Sittengeschichte des Ersten Weltkrieges, Hanau 1981.

Kappeler, Susanne, Der Wille zur Gewalt. Politik des persönlichen Verhaltens, München 1994.

Kittel, Lisa u.a., „Deutschland ist ein Paradies für Menschenhändler“ published 5 April 2013, URL: http://www.welt.de/politik/deutschland/article115023141/Deutschland-ist-ein-Paradies-fuer-

Menschenhaendler.html (las checked 19 July 2015).

Koelbl, Susanne, „Zwangsprostitution im Zweiten Weltkrieg: Japans Schande“, pubished 03 September 2013, URL: http://www.spiegel.de/panorama/japan-im-zweiten-weltkrieg-die-schande-der-trostfrauen-a-919909.html, last checked 20 July 2015.

Kühne, Thomas, Kameradschaft. Die Soldaten des nationalsozialistischen Krieges und das 20. Jahrhundert, Göttingen 2006.

Lagebericht vom 2.10.1942. Blatt 16 zum Lagebericht, Bundesarchiv/Militärarchiv RW35-1221.

Latzel, Klaus, Tourismus und Gewalt. Kriegswahrnehmungen in Feldpostbriefen, in: Heer, Hannes und Naumann, Klaus (ed.), Vernichtungskrieg. Verbrechen der Wehrmacht 1941-1944, p. 447-460.

Leitender Sanitätsoffizier beim Militärbefehlshaber im Generalgouvernement, Spala, den 2. Oktober 1940, Bericht über die Bordelle für Heeresangehörige im Gen.-Gouv., Bundesarchiv/Militärarchiv RH12-23-1818.

Lohner, Margret, Die Prostitution und ihre Bedeutung in der venerologischen Sicht, Diss., München, 1990.

Meinen, Insa, Wehrmacht und Prostitution im besetzten Frankreich, Bremen 2002.

Merkblatt fur Soldaten. Merkblatt 53/13. „Deutscher Soldat! Merkblatt zur

Verhütung von Geschlechtskrankheiten“, Bundesarchiv Militärarchiv RH12-23-71.

Mühlhäuser, Regina, Eroberungen. Sexuelle Gewalttaten und intime Beziehungen deutscher Soldaten in der Sowjetunion, 1941-1945, Hamburg 2010.

Neitzel, Sönke und Welzer, Harald, Soldaten. Protokolle vom Kämpfen, Sterben und Töten, Frankfurt am Main 2011.

Oberkommando des Heeres, Generalstab des Heeres, Generalquartiermeister, Az. 1271 IV b (Ila), Nr. I/13016/42, HQuOKH, den 20. März 1940, Betr.: Prostitution und Bordellwesen in den besetzten Ostgebieten, Bundesarchiv/Militärarchiv RH 12-23-1818.

Oberkommando der Wehrmacht. Az. B49 Tgbnr. 71/42 Ch W San. Abschrift. Betr.. Bekämpfung der Geschlechtskrankheiten, Berlin, 27. Januar 1943, Bundesarchiv/Militärarchiv RH12-23-1818.

Paul, Christa, Zwangsprostitution. Staatlich errichtete Bordelle im Nationalsozialismus, Berlin 1994.

Plassmann, Max, Wehrmachtbordelle. Anmerkungen zu einem Quellenfund im Universitätsarchiv Düsseldorf, in: Militärgeschichtlichen Forschungsamt Potsdam (ed.), Militärgeschichtliche Mitteilungen, MGM Band 62 (Heft 1), München 2003.

Respondek, Anne S., „Gerne will ich wieder ins Bordell gehen“ – Ein Beitrag über die „freiwillige Meldung“ ins Wehrmachtsbordell, Dresden 2014 (unpublished Master thesis).

Richtlinien fur die Einrichtung von Bordellen in den besetzten Gebieten. Armeeoberkommando 6 O.Qu./IVb, A.H.Qu., am 23. 7. 1940, Anlage 4, Bundesarchiv/Militärarchiv RH20-6-1009.

Richtlinien für die Einrichtung von Bordellen in den besetzten Gebieten. Armeeoberkommando 6 O.Qu./IVb, A.H.Qu., am 23. 7. 1940, Anlage 11, Bundesarchiv/Militärarchiv RH20-6-1009.

Scherber, Gustav, Die Bekämpfung der Geschlechtskrankheiten und der Prostitution, Wien 1939.

Schikorra, Christa, Kontinuitäten der Ausgrenzung. „Asoziale“ Häftlinge im Frauen-Konzentrationslager Ravensbrück, Berlin 2001.

Schmölzer, Hilde, Die Frau. Das gekaufte Geschlecht. Ehe, Liebe und Prostitution im Patriarchat, Bad Sauerbrunn 1993.

Seidler, Franz, Prostitution, Homosexualität, Selbstverstümmelung. Probleme der deutschen Sanitätsführung 1939 – 1945, Neckargmünd 1977.

Sommer, Robert, Das KZ-Bordell, Paderborn 2009.

Sommer, Robert, Der Sonderbau. Die Errichtung von Bordellen in den nationalsozialistischen Konzentrationslagern, Berlin 2006.

Spongberg, Mary, Feminizing veneral disease – The Body of the Prostitute in Nineteenth-Century Medical Discourse, London 1997.

Tatbestand „Menschenhandels zum Zweck der sexuellen Ausbeutung“, §232 StGB, http://dejure.org/gesetze/StGB/232.html, last checked 04 April 2016. English version quoted after Prof. Dr. Michael Bohlander, Gesetze im Internet (online) <https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/englisch_stgb/englisch_stgb.html#p2086> last checked Feb. 13th 2021.

Umbreit, Hans, Deutsche Militärverwaltungen 1938/39. Die militärische Besetzung der Tschechoslowakei und Polens, Stuttgart 1977.

Wetzel, Harald, Täter. Wie aus ganz normalen Menschen Massenmörder werden, Frankfurt am Main 2005.

Zipfel, Gaby, Ausnahmezustand Krieg? Anmerkungen zu soldatischer Männlichkeit, sexueller Gewalt und militärischer Einhegung, in: Eschebach, Insa, Mühlhäuser, Regina (ed.), Krieg und Geschlecht. Sexuelle Gewalt im Krieg und Sex-Zwangsarbeit in NS-Konzentrationslagern, p. 55-75.

[1]Schmözer, Die Frau, p. 291-293.

[2]The title references a statement given by Maria K. in the file „Maria K.„, p. 85. This essay is a radically shortened version of my master thesis, which was mentored by Dr. Phil. Habil. Sonja Koch and PD Dr. Manfred Nebelin, and handed in to the faculty of philosophy at TU Dresden in 2014.

[3]Cf. Hirschfeld, Gaspr, Sittengeschichte des Ersten Weltkriegs, p. 231-281 and Cf. Eckart, Plassmann, Verwaltete Sexualität, p. 100-107, and Cf. Beck, Wehrmacht und sexuelle Gewalt, p. 106.

[4]Cf. Sommer, Das KZ-Bordell, p. 111-161.

[5]Cf. Paul, Zwangsprostitution, p. 117-131.

[6]Cf. Paul, Zwangsprostitution, p. 106.

[7]Cf. Mühlhäuser, Eroberungen, p. 215.

[8]Cf. Mühlhäuser, Eroberungen, p. 232-234.

[9]Cf. Seidler, Prostitution, Homosexualität, Selbstverstümmelung, p. 151, p. 182 f.

[10]Cf. Sommer, Der Sonderbau, p. 65-82.

[11]Frauen als Beute, Minute 10.00.12.44 – 10.00.16.44 and 10.00.34.14 – 10.00.36.12. Christa Paul also consulted the file in her work: Paul, Zwangsprostitution, p. 105 f.

[12]Neitzel, Welzer, Soldaten, p. 217-229.

[13]Der Heeresarzt im Oberkommando des Heeres, Gen St d H/Gen Qu Az. 265 Nr. 17150=4o, Abschrift betreffend: Prostitutuin und Bordellwesen im besetzten Gebiet Frankreichs, H Qu OKH, dated 1940-07-16, Bundesarchiv/Militärarchiv RH12-23-1371. This directive was also in power in Poland at the time of its occupation.

[14]Case File Maria K., p. 59, p. 43: Der Reichsminister des innern, IV. G 3437/39 5670, issued 1939-09-18 in Berlin, Betrifft: Bekämpfung der Geschlechtskrankheiten, Bundesarchiv/Militärarchiv RH12-23-1818, especially p. 1:

If a person, who is strongly suspicious to have venereal diseases, fails to follow the instruction to undergo a medical check at a place made known to them at the stipulated time, they are to be reported to the local police immediately. Persons who continuously resist instructions given by the health authorities can be taken into preventive custody by the police. In these cases, the health authorities are obliged to pass on relevant documents to the criminal police department in charge.

[15]Case File Maria K., „andernfalls ich in Vorbeugehaft genommen werde oder in ein Konzentrationslager unter-gebracht [sic] werde“ (otherwise I would be taken into preventive custody or a concentration camp), p. 43.

[16]Leitender Sanitätsoffizier beim Militärbefehlshaber im Generalgouvernement, issued 1940-10-02 in Spala, Bericht über die Bordelle für Heeresangehörige im Gen.-Gouv., Bundesarchiv/Militärarchiv RH12-23-1818: „Die Mädchen haben Anweisung, nur mit Kondom zu verkehren.“ (The girls are instructed to only have sex with a condom)

[17]Der Oberbefehlsthaber der 15. Armee, A. H. Qu., issued 1941-07-12. Betr.: Bekämpfung der Geschlechtskrankheiten, Abschrift, Bundesarchiv/Militärarchiv RH20-15-156: „Dirnen werden nicht selten durch Drohungen und sogar misshandlungen zur Duldung des Verkehrs ohne Kondom gezwungen. Das ist saudumm und straftbar.“ (Not uncommonly, prostitutes are pressured into enduring to have sex without a condom through threats, or even physical abuse. This is wicked dumb and liable to prosecution.) and cf. Meinen, Wehrmacht und Prostitution, p. 210 f.

[18]Cf. Meinen, Wehrmacht und Prostitution, p. 115-119, 122-130.

[19]Cf. Seidler, Prostitution, p. 121-126.

[20]Prostitutes who were suspected to have sexual intercourse with German soldiers in spite of an infection, had to face severe consequences, e.g. in France. Feldkommandatur 581, Verwaltungsstab, Vw Gr. ½ to the Kreiskommandaturen, Rennes, St.-Malo, Fourgéres, Redon, Betr.: Überwachung der Prostitution – here Polizeiliche Maßnamen und Strafen, issued 1941-04-04 in Rennes, Bundesarchiv/Militärarchiv RH6-444:

In special cases, it is possible that, if an assessment by the medical officer in charge comes to this conclusion, the facts can be interpreted as a criminal offense against the ‚Gesetz zur Bekämpfung der Geschlechtskrankheiten‘ (law against venereal diseases) and therefore taken to military court. These measures can be considered: Confinement in a detention centers, placement under police supervision, assignment to an enforced stay somewhere, &c.

[21]These stays were enforced in France, as well as the Soviet Union and occupied Poland: Der Heeresarzt im Oberkommando des Heeres, GenStdH/Genu, Az. 1271 (Iia), Nr. I/13017/42, HqzOKH, issued 1942-03-20, Bezug: Verfügung OKH/GenStdH/GenQu/Az.: 1271 IV b (Iia) Nrr. I/13016/42 issued 1942-03-20, Betr.: Prostitution:

Prostitutes who have a venereal disease, or are under suspicion to have one, are to be taken to a civil hospital immediately. The city administration is obligated to keep infected prostitutes in custody until their full recovery.

As well as:Der Reichsminister des Innern, IV g 3437/39 5670, issued 1939-09-18, Betrifft: Bekämpfung der Geschlechtskrankheiten, Bundesarchiv/Militärarchiv RH12-23-1818, p. 1:

If an infectious venereal disease is detected in a person whose sexual partners frequently change, then voluntary medical treatment will be unnecessary, since it is to be expected that the infected female will have sex in spite of an ongoing risk of infection during treatment.

[22]Cf. Formular für die Kontrolle der Hygieniker im Gernalgouvermement. Berichtformular. Bundesarchiv/Militärarchiv RH12-23-1818 and Der Reichsminister des Innern, IV g 3437/39 5670, issued 1939-09-18, Betrifft: Bekämpfung der Geschlechtskrankheiten, Bundesarchiv/Militärarchiv RH12-23-1818 and cf. Scherber, Gustav, Die Bekämpfung der Geschlechtskrankheiten und der Prostitution, Wien 1939, p. 182, and Corbin, Wunde Sinne, p. 147 and cf. Spongberg, Feminizing Venereal Disease, p. 15-61 and p. 141-183, and cf. Lohner, Die Prostitution, p. 30-35.

[23]See also: Der Oberbefehlsthaber des Heeres, Nr. 8840/41 PA2 (I/Ia) Az. 15, H Qu OKA issued 1941-09-06, Geheim, Betr.: Selbstzucht, Anlage 1 Nr. 18497/40, 31. Juli 1940, Bundesarchiv/Militärarchiv RH 12-23-1391: „[…] erscheint es vom hygienischen und disziplinären Standpunkt aus zweckmäßiger, geeignete, unter ärztlicher Kontrolle stehende Bordelle freizugeben, als der Möglichkeit Vorschub zu leisten, daß der deutsche Soldat der weilden prostitution zum Opfer fällt.“ (Seen from a hygenic and disciplinary angle, it would seem more advisable to clear brothels under medical supervision for visits rather than risk the German soldier to fall victim to unruly prostitution.)

[24]Merkblatt für Soldaten, Merkblatt 53/13, Deutscher Soldat! Merkblatt zur Verhütung von Geschlechtskrankheiten, Bundesarchiv/Militärarchiv RH12-23-71:

Avoid contact with easy women! They are almost always suffering from venereal disease! If you have had extramarital intercourse with a woman in a careless moment, do not recklessly elude your sanitary obligations. In any case, remember the name, address, residence and physical features of the woman you had sex with.

[25]Ibid.:

A soldier with a venereal disease cannot do military service; disability for service brought on by their own fault, however, is unworthy of a German soldier! Your fatherland expects not only your full soldierly service, but also that you start a healthy family and become father to healthy children!

[26]Richtlinien für die Einrichtung von Bordellen in den besetzten Gebieten, Armeeoberkommando 6 O.Qu./IVb, A.H. Qu. Issued 1940-07-2, attachment 4, Bundesarchiv/Militärarchiv RH20-6-1009:

Thereafter, the military sanitation office („Sanitätsstube“) is immediately to be consulted. Every soldier must know that he is held accountable for his health for the service. Negligence regarding the health restrictions constitutes a violation of official instructions and will be punished.

And cf. Richtlinien für die Einrichtung von Bordellen in den besetzten Gebieten, Armeeoberkommando 6 O.Qu./IVb, A.H. Qu. Issued 1940-07-23, attachment 11, Bundesarchiv/Militärarchiv RH20-6-1009; also „Der Sanitätsoldat“, Paragraphs on ‚Schutzbehandlung‘, p. 35, Bundesarchiv/Militärarchiv RH12-23-994; also cf. Oberkommando der Wehrmacht, Az. B49 Tgbnr, 71/42 Ch W San, Abschrift, Betr.: Bekämpfung der Geschlechtskrankheiten, issued 1943-01-27 in Berlin, Bundesarchiv/Militärarchiv RH12-23-1818.

[27]Cf. Seidler, Prostitution, p. 107F, and cf. Der Oberbefehlshaber der 15. Armee, A.H. Qu., issued 1941-07-12, Betr.: Bekämpfung der Geschlechtskrankheiten, Abschrift, Bundesarchiv/Militärarchiv RH20-15-156.

[28]See: Der Oberbefehlshaber des Heeres, Nr. 8840/41 PA2 (I/Ia) Az. 15, H Qu OKH, issued 1941-09-06, Geheim, Betr.: Selbstzucht, Bundesarchiv/Militärarchiv RH12-23-1371:

Recently, there have been incidents during visits to the brothels in the occupied regions that are abhorrent to a soldier’s sense of honour , let alone that of an officer. There have been numerous displays of unworthy demeanour. Foul and unworthy excesses have to be avoided through repeated educational measures in a repeated fashion and with emphasis appropriate for the issue.

[29]See: Der Oberbefehlshaber des Heeres, Nr. 8840/41 PA2 (I/II) Az. 15, H Qu OKH issued 1941-09-06, Geheim. Betr.: Selbstzucht, Attachment 1 Nr. 18497/40, issued 1940-07-31, Bundesarchiv/Militärarchiv RH12-33-1371:

In any case, the issue cannot be resolved by prohibition of sexual actions in the occupied regions. Such a ban would, among other things, doubtlessly create an increase in the number of rapes (euphemistically phrased „Notzuchtverbrechen“) and violations of §175 (i.e. §175 of the German Criminal Code, which outlawed homosexual actions among men until its cancellation in 1994).

[30]Cf. Beck, Wehrmacht und sexuelle Gewalt, p. 6.

[31]Cf. Gertjejanssen, Victms, Heroes, Survivors, p. 151; Cf. Beck, Wehrmacht und sexuelle Gewalt, p. 193f.

[32]Wehrkreisarzt XVIII, Schreiben an den Heeressanitätsinspekteur in Berlin, 1945-01-03, NARA RG-242 78/189, Bl. 761f, here Bl. 751, referrenced after Mühlhäuser, Eroberungen, p. 236:

The disadvantages of brothels are the overall repulsive mass processing, and the fact that large numbers of young soldiers and those, who would hardly engage in this otherwise, are taken along by comrades and practically coerced into having intercourse with prostitutes, and all these evident disadvantages are in no way compensated by the existing means of exerting control.

And: Vossler, Frank, Propaganda in die eigene Truppe. Die Truppenbetreuung in der Wehrmacht 1939-1945, Paderborn 2005, p. 340, referrenced after Mühlhäuser, Eroberungen, p. 237: Troup physician Walter Camerer constistutes in May 1943: This downgrading of women into females, this deliberate stimulation to be sensual is not without effect. („Diese Herunterziehung der Frau zum Weib, dieses bewute Anstacheln zur Sinnlichkeit, bleibt nicht ohne Wirkung.“), likewise: Disziplinarbericht der 8. Zerstörerflotte „Narvik“ fpr die Zeit vom 1. Juli 1942 bis 1. September 1943, BA/MA, RM 58/39, referrenced after Neitzel, Soldaten, p. 227:

The usage of the brothels has taken on a scale that is no longer consistent with a clean soldierly development of personality. What is more is that the brothels are not only frequented by the youngest soldiers, the eighteen to twenty-year-olds, but in large quantity also by corporals and staff sergeants. The sense of order and cleanliness, the perception of women, and the understanding of the meaning of healthy family life for the future of our people is badly affected by this.

[33]See: Der Oberbefehlshaber des Heeres Nr. 8840/41 PA2 (I/II) Az. 15, H Qu OKH issued 1941-09-06, Geheim. Betr.: Selbstzucht, Attachment 1 Nr. 18497/40, 1940-07-31, Bundesarchiv/Militärarchiv RH12-23-1371:

The longer the stay of German troups is in the occupied regions, the more orderly and peace-like the circumstances get under which a soldier lives there and does his duty there, the more do the issues of sexuality with all their conditions and consequences beckon to be seriously taken into account. Considering the diverse predisposition of people, it is impossible to avoid sexual tensions and predicaments to arise that cannot, and should not be denied. In any case, the issue cannot be resolved by prohibition of sexual actions in the occupied regions.

[34]Case file p. 89:

(…) considered to be an asocial woman. She often broke the rules at the brothel to which she was fordefully placed in (the original reads „zwangsweise untergebracht“ which is crossed out and replaced with „eingewiesen“ [i.e. committed] in handwriting). She continuously disregarded the health authorities‘ instructions, as well as the prohibitive rules and obligations the criminal police have given her. Reprimands and cautioning were unsuccessful. She does not warrant unobjectionable behaviour in the future, the more so as the experience one had here shows her defiant tendencies. Her detainment in preventive custody is a necessity in the interest of the German national character and people’s health‘ (Volkstumspflege und Volksgesundheit), because she is to be considered a source of infection in the spreading of venereal diseases. Her being at large would be irresponsible from the perspective of the security police. Judging from her overall behaviour to date, no improvement can be expected in K. without strict education at camp.

[35]This kind of profiles, reports, and social prognoses regarding „asocial“ individuals and women suspected of prostitution is not restricted to singular cases, but rather made in accordance with a classification schema used by almoners and criminal police: Cf. Ayaß, Asoziale im Nationalsozialismus, p. 188-196, also cf. Schikorra, Kontinuitäten der Ausgrenzung, p. 42-51, p. 105-113.

[36]Cf. Clauß, Rasse und Seele, pp. 171-186, esp. p. 175 f.

[37]Cf. Meinen, Wehrmacht und Prostitution, p. 157-164; Cf. Umbreit, Deutsche Militärverwaltungen, p. 197-200.

[38]Case file, p. 33: „bitte ich, sie auf Grund des Erlasses des Reichsstatthalters, wonach Polen, die den Geschlechtsverkehr mit Reichsdeutschen ausüben, in ein Bordell gebracht werden können, das Weitere in dieser Hinsicht zu veranlassen“ (I ask, on the grounds of the decree from the Reich governer, which says that Polish who have sex with citizens of the German Reich can be brought to a brothel, to arrange for everything else in that regard.), and case file p. 15: „[…] als sie wieder mit deutschen Soldaten Umgang pflog. […] Ich bitte ihre Einweisung in ein Bordell nunmehr zu veranlassen.“ ([…] when she was in contact with German soldiers again. […] I ask for the arrangements for her admission into a brothel to be made.)

[39]Leitender Sanitätsoffizier beim Militärbefehlshaber im Generalgouvernement, Spala, den 2. Oktober 1940, Bericht über die Bordelle für Heeresangehörige im Gen.-Gouv., Bundesarchiv / Militärarchiv RH12-23-1818.

[40]Oberkommando des Heeres, Generalstab des Heeres, Generalquartiermeister, Az.. 1271 IV b (Iia), Nr. I/12016/42, HquOKH, issued 20 March 1940, Betr.: Prostitutuin und Bordellwesen in den bestzten Ostgebieten, Bundesarchiv/Militärarchiv RH 12-23-1818: „Die Gefahren einer solchen versteckten Prostitution bestehen nicht allein in der stark vermehrten Möglichkeit der Ansteckung, sondern öffnen erfahrungsgemäß auch dem fahrlässigen Verrat militärischer Geheimnisse viele Wege.“ (The danger of such hidden prostitution is not only the threat of increasingly high opportunities for infection, but also that it opens up many ways for negligent betrayal of military secrets)

[41]Div.-Arzt 162. Inf.Div., o.U., den 12.3.43, Betr.: Bordelle auf dem Truppenübungsplatz Neuhammer. Bezug: Ferngespräch des stellv. Wehrkreisarztes VIII mit dem Adjutanten des Div.-Arztes am 11.3.43. An den Korpsarzt beim stellv. Gen. Kdo. VIII A.K. (Wehrkreisarzt VIII) Breslau. Bundesarchiv/Militärarchiv, RH 26-162-58: In the period 4th – 10th March 1943, there was an average of 22.6 punters per prostitute in the East division, and 25.7 in the West division. On Sunday, 7th March 1943, there was a peak of 27.6, respectively 46.5 punters per prostitute. Since the brothels had opened only seven days earlier, the doctor assumed that an increase in number could be expected. In addition to this, it has to be considered that a number of women will always not be available due to menstruation, which means that the number of visitors per prostitute will actually be higher that indicated above.“; Leitender Sanitätsoffizier beim Militörbefehlshaber im Generalgouvernement, Spala, den 2. Oktober 1940, Bericht über die Bordelle für Heeresangehörige im Gen.-Gouv., Bundesarchiv/Militärarchiv RH12-23-1818: „Die Beziehungen der Dirnen zu den wechselnden Besuchern (mitunter 20-30 am Tage) sind sachlich-wirtschaftlicher Art. […] Die Besuchszeiten sind meist von 16-24 Uhr.“ (The connections between the harlots and their various visitors [sometimes 20-30 a day] are of a functional and economical nature. The visiting hours are mostly between 4 pm – 12 pm.)

[42]Drolshagen, Der freundliche Feind, p. 331 f.; Cf. Zipfel, Ausnahmezustand Krieg?, p. 66f.; Halbmayr, Sexualisierte Gewalt, p. 331 f,; Cf. Mühlhäuser, Eroberungen, p. 85-100.

[43]Der Oberbefehlshaber der 15. Armee, A.H.Qu., den 12.7.41. Betr.: Bekämpfung der Geschlechtskrankheiten, Abschrieft, Bundesarchiv/Militärarchiv RH20-15-156: Our guys must know that only the scum of female population in the occupied countries will engage with them. It does not make a difference, if this happens in exchange for money, or not. The German soldier has to consider it to be beneath his dignity, to engage with such lowlifes.; BA-ZNS p. 269, Gericht der 7. Pz. Div. BI, 18-23, Feldurteil vom 19. August 1941, referrenced after Beck, Wehrmacht und sexuelle Gewalt, p. 288: „wenn, wie es hier der Fall ist, die verletzte Frauenperson einem Volk angehört, dem der Begriff der Geschlechtsehre der Frau nahezu entschwunden ist.“ (if, as is the case here, the raped woman belongs to a people that has almost entirely lost a sense of ‚Geschlechtsehre‘ [dignity of sex].); BA-ZNS p. 152, Gericht der 35. Inf. Div., BI. 9F: Feldurteil vom 24. Oktober 1943, here p. 9, referrenced after Beck, Wehrmacht und sexuelle Gewalt, p. 290: The very high penalty threatened by § 176 RStGB [i.e. Reichsstrafgesetzbuch, the criminal code] is supposed to protect German women against criminal attacks against their female honour. This aspect is inapplicable when it comes to Russian women. They are not that fragile that an experience like the one the accused has caused them would leave them with lasting psychological damage.

[44]SRA 2386, 12.12.1041, TNA, WO 208/4126, referrenced after Neitzel, Soldaten, p. 225: „Göller: „Ich habe Bordeaux erlebt. Das ganze Bordeaux ist ein einziger Puff.“ (I have experienced Bordeax. The entire region of Bordeaux is just a brothel.); Wehrmachtsangehöriger Niwiem, Abhörprotokoll SRA 1227, 1.2.1941, TNA, WO 208/4122, quoted after Neitzel, Soldaten, p. 226: „Ich habe gesehen, wie unsere Jäger mitten in einem Lokal Mädels gepackt haben, über den Tisch gelegt und – fertig! Verheiratete Frauen auch!“ (I saw how our riflemen grabbed girls in the middle of an establishment, layed them on a table and – done! Married women, too!); Room Converstation Müller – Reimbold, v. 22.3.1945, NARA, RG 165, Entry 179, Box 530, referrenced after Neitzel, Soldaten, p. 227 f.: Then we slapped her ass with a drawn sidearm. Then we fucked her, then we threw her out, then we shot at her when she was lying on her back, then we aimed with grenades. And every time they hit near her, she screamed. In the end she croaked and we disposed of the body.; Room Conversation Czosnowski – Schultka, 2.4.1945, NARA, Box 458, p. 438 f., quoted after Neitzel, Soldaten, p. 228: „Das waren zwei Männer, zwei Väter; der eine hatte zwei Töchter. Dann haben sie die beiden Töchter gevögelt, ordentlich durchgebürstet, dann die über den Haugen geschossen, die beiden Töchter.“ (They were two men, two fathers; one had two daughters. Then they screwed the two daughters, really banged them, then gunned them down, the two daughters.); Wehrmachtsangehöriger Felbert und Kittel, Abhörprotokoll SRGG 1086, 28.12.1944, TNA, WO 208/4169, quoted after Neitzel, Soldaten, p. 153: „Felbert: ‚Was wurde aus den jungen hübschen Mädchen? Wurden die zu einem Harem zusammengestellt?‘ Kittel: ‚(…) Die Weibersache, das ist ein ganz düsteres Kapitel.'“ (Felbert: What became of the young and pretty girls? Were they assembled in a harem? Kittel: This women thing, that is a pretty dark chapter.)

[45]Mühlhäuser, Eroberungen, p. 87, p. 95-105; Cf. Neitzel, Soldaten, p. 105, p. 153, p. 158, p. 162-167, p. 217-229.

[46]Wehrmachtsangehöriger Sauermann, Abhörprotokoll Room Conversation Sauermann – Thomas, 5.8.1944; NARA, RG 165, Entry 179, Box 554, quoted after Neitzel, Soldaten, p. 223: „Die Reichskanzleiführer, ich weiss nicht, aber die Sache war, jedenfalls die Gestapo hat die Finger da mit im Spiel gehabt, wir nahmen von unseren Krediten, die uns das Reich gab für den Bau von … Anlagen, gab das Werk noch einen Zuschuss für den Bau eines Bordells, eines Puffs. Wir nannten das eine B-Baracke. Wie ich wegging, war das fertig, nur die Weiber fehlten noch. Die Leute liefen in dem Ort rum und pufften da jedes deutsche Mädchen an, und das wollte man vermeiden, die bekamen da ihre Französinnen, ihre Tschechinnen, das ganze Volk kam da rein, die ganzen Weiber.“ (The leaders at the Chancellery of the Reich, I don’t know, but the thing is, at least the GeStaPo had a hand in this. We made use of our credits, the ones the Reich gave to us for the construction of … facilities. The works gave us a subsidy to build a brothel, a bordello. We called it a B-barrack. As I left, it was all done, only missing the women. The guys were roaming the area to fuck any German girl, and this was meant to be avoided. They got their French women, their Czech women, the whole bunch went in there, all the women.)

[47]Beckermann, Jenseits des Krieges, p. 134, quoted after Beck, Wehrmacht und sexuelle Gewalt, p. 115: „Natürlich richtete man in den grösseren Ortschaften Bordelle ein. […] das waren russische Frauen […] und zum Teil … ja. Sie wurden nicht gezwungen, das war ihr Beruf.“ (Of course, brothels were established in the bigger settlements. […] they were Russian women […] and partly … well. They were not being forced, this was their profession.)

[48]Wehrmachtangehöriger Wallus, Abhörprotokoll SRA 735, 14. 10. 1940, TNA, WO 208/4120, referrenced

after Neitzel, Soldaten, p. 221

[49]Lagebericht vom 2.10.1942. Blatt 16 zum Lagebericht, Bundesarchiv / Militärarchiv RW35-1221.

[50]Cf. Mühlhäuser, Eroberungen, p. 94f., cf. Neitzel, Soldaten, p. 163-5.

[51]Cf. Kühne, Kameradschaft, p. 175, cf. Mühlhäuser, Eroberungen, p. 93f.

[52]Cf. Latzel, Tourismus und Gewalt, p. 448; Cf. Bartjes, Das Militär, p. 19-37; Cf. Wetzel, Täter, p. 202; Cf Kühne, Kameradschaft, p. 97-113.

[53]Zum Privaten und Politischen cf. Kappeler, Der Wille zur Gewalt, p. 32-47.

[54]Richtlinien für die Einrichtung von Bordellen in den besetzten Gebieten, Armeeoberkommando 6 O.Qu./IVb, A.H.Qu., July 23rd 1940, Bundesarchiv/Militärarchiv RH20-6-1009: „Der in den Richtlinien angegebene Preis von 3,- RM soll ein Mindestpreis sein. Endgültige Festsetzung erfolgt durch die Kommandantur. Hierbei ist zu beachten, daß der Preis so gestellt sein muß, daß dadurch nicht ein Anreiz zum Bordellbesuch erfolgt, sondern daß er in jedem Fall eine zu überlegende Ausgabe bedeutet.“ (The price of 3 RM indicated in the regulations constistutes a minimum price. The ultimate pricing is to be done by the commandant’s office. The pricing has to be done in a way that does not make the price a motivator for the visit to a brothel, but makes it a considerable expense.)

[55]Cf. Meinen, Wehrmacht und Prostitution, p. 156.

[56]Lagebericht vom 2.10.1942. Blatt 16 zum Lagebericht, Bundesarchiv/Militärarchiv RW35-1221.

[57]Cf. Meinen, Wehrmacht und Prostitution, p. 179-92: „freie“ Prostituierte wurden in Lager inhaftiert, frei kamen sie nur, wenn sie eine anstehende Eheschließung oder eine bezahlte Anstellung vorweisen konnten (beides dürfte aus dem Lager heraus schwer zu organisieren gewesen sein), sich für einen Arbeitseinsatz ins Reich meldeten oder eben die Meldung in ein Wehrmachtsbordell tätigten. Andere freie Prostituierte wurden genötigt, im Wehrmachtsbordell anzuschaffen, andernfalls ihnen Lagerhaft, Einsperrung oder weitere Verfolgung (auch KZ) drohte. („free“ prostitutes were kept at camps and were only released if they were able to produce proof of an upcoming marriage or paid job [both of which would be reasonably hard to get proof of while in a camp], or if they volunteered for a work assignment for the Reich, or if they requested joining a Wehrmacht military brothel. Other free prostitutes were compelled to be prostituted at a Wehrmacht military brothel, or otherwise to be taken a camp prisoner, arrested, persecuted further [including concentration camps].

[58]Cf. Paul, Zwangsprostitution. (Paul puts the brothels into context with sexualised violence); Beck, Wehrmacht und sexuelle Gewalt, p. 105-17 (Beck, too, puts the brothels into context with sexualised violence during the war (p. 331) but classifies only a few cases as cases of forced prostitution (p. 114)); Mühlhäuser, Eroberungen, p. 214-240.

[59]Seidler, Prostitution, Homosexualität, Selbstverstümmelung.

[60]Meinen, Wehrmacht und Prostitution.

[61]Plassmann, Wehrmachtsbordelle, p. 157-173.

[62]Gertjejanssen, Victims, Heroes, Survivors.

[63]Plassmann, Wehrmachtsbordelle, p. 169: „Natürlich hat die Not der Kriegszeit vielfach dazu geführt, daß sich die Frauen nicht wirklich freiwillig verpflichteten. Dem entspricht zum Beispiel die Beobachtung, daß sich im Winter mehr Frauen meldeten als im Sommer, da die Wehmachtsbordelle über eine ausreichende Kohleausstattung verfügten […].“ (Naturally, the hardship of war time has often lead to women registering not entirely voluntary. An example of this is the observation that more women registered in winter than in the summer, because the Wehrmacht brothels had a satisfactory supply of coal.) But what does it mean if women’s registration into the brothels was ’not entirely voluntary‘ but born out of necessity, and if later they are not free to leave, if they have to have sexual intercourse because they must not quit? What conclusion can be drawn from this in respect of classification? Several times Plassmann speaks of ‚labour‘ at the brothel, even concerning the few cases involving direct compulsion that he does acknowledge, e.g. ibid. p. 168: „Natürlich sind auch Fälle der Ausübung direkten Zwanges auf Frauen nachweisbar, in einem Bordell zu arbeiten.“ (Naturally, instances of direct compulsion on women to work in a brothel are certifiable.) Using the term ‚work‘ for forced prostitution is minimisation. Forced prostitution means being subjected to a series of rapes.

[64]Cf. Meinen, Wehrmacht und Prostitution, p. 214. In her work, Insa Meinen has accomplished an outstanding analysis of Wehrmacht brothels in France, as well as a description of the reprisals women being persecuted had to face as the result of patriarchial gender relations. It is all the more curious that there is no classification into the context of sexualised violence. The reason she gives for this is that the Wehrmacht did not persecute the women in order to force them into having sex with the soldiers, but to monitor the prostitution contact between German soldiers and French women, as those were not condoned of aside from the Wehrmacht brothels. While this may have been the case concerning the social environment outside the brothels, is certainly was not as far as recruitment and the sitiuation in the brothel itself are concerned, which is illustrated by a „Zwangsaufenthaltsklausel“ (compulsory stay clause), threatening with concentration camps, punishment of women who defied imposing soldierly Johns, being forbidden to leave the brothel, ‚employment contracts‘ that were not unilaterally terminable, &c. (p. 204-213). Moreover it is irrelevant to the definition of forced prostitution whether or not a perpetrator (primarily or secondarily) intended said forced prostitution.

[65]Plassmann, Wehrmachtsbordelle, p. 164, here Plassmann speaks of ’naturally occurring escalations of any kind at the brothels‘ („natürlich vorkommende ‚Ausschreitungen‘ aller Art in den Bordellen“) which begs the question why escalations against women ’naturally‘ (have to?) occur, and why Plassmann frames the term for escalations (Ausschreitungen) in inverted commas.

[66]Ibid, p. 167: „Die Tätigkeit der Prostituierten in Wehrmachtsbordellen trug insgesamt die Züge eines fast normalen Arbeitsverhältnisses. Am Anfang stand eine Meldung der arbeitswilligen [sic!] Frau selbst (Fußnote: Oder ihres Zuhälters. Zu dieser Frage läßt sich anhand der vorliegenden Quellen keine Aussage machen.), die dann nach Prüfung der gesundheitlichen und sonstigen Eignung und des Alters durch deutsche und französische Stellen einen Arbeitsvertag unterschrieb. Dieser konnte eine Laufzeit von einem bis drei Monate haben. Er verlängerte sich nach Abauf dieser Zeit automatisch, sofern er nicht gekündigt wurde. Dabei war das Kündigungsrecht nicht einseitig, während ein Verlassen des Bordells während der Verpflichtungszeit strafrechtlich verfolgt wurde. […] ebenso die starke Eingenzung der Bewegungsfreiheit der Frauen während ihrer Beschäftigung im Bordell: Sie durften nicht unkontrolliert das Haus verlassen […]“

(The employment of a prostitute in a Wehrmacht brothel overall resemled an almost normal employment relationship. It started with a request made by the woman willing to work [sic!] herself [Footnote: or her pimp. This question cannot be answered based on the sources at hand], who then, after her qualification based on health and age being evaluated by German and French authorities, signed an employment contract. It could have a term of one up to three months. It renewed itself automatically unless terminated. The right to terminate the employment was not unilateral, while leaving the brothel during the contract term was punishable by law. […] and the women’s strict restriction of freedom of movement during their employment at the brothel: They were not allowed to leave the house without supervision.)

It remains unclear where this is supposed to be a normal work relationship. How the request made by a women came to be is also never questioned there. Also, the author does not reflect on what it means for a woman to not be able to terminate her contract, nor leave the brothel: it means she has to have sex with men who she does not wish to have sex with, simply because there is a contract that forces her to do it. What is this, if not forced prostitution?

[67]Ibid, p. 168: Natürlich sind auch Fälle der Ausübung direkten Zwanges auf Frauen nachweisbar, in einem Bordell zu arbeiten. Aber aus dem Bemühen [sic!], die Frauen am Arbeitsplatz zu halten, spricht deutlich die Zwangslage der Wehrmacht: Es war nicht ohne weiteres möglich, die notwendige Anzahl von Frauen gleichsam als Kriegsbeute in die Bordelle abzuordnen. Die Prostitution in den Wehrmachtsbordellen in Frankreich kann also sicher nicht ohne weiteres nur mit Ausübung von Gewalt gegen Frauen des unterlegenen Gegners gleichgesetzt werden, zumal bei der Anwerbung der Frauen französische Zuhälter oder Kuppler tätig waren, die ihren eigenen Profit suchten.“

(Naturally, instances of direct compulsion on women to work in a brothel are certifiable. But the endeavours [sic!] to keep the women at their place of employment speak clearly of the predicament of the Wehrmacht: It was not easily possible to send the necessary number of women as spoils of war into the brothels. Prostitution within the Wehrmacht brothels in France can therefore not sumply be equated with violence against the women of an inferior enemy, especially since the recruitment of the women featured French pimps and match-makers looking for their own benefit.)

Justifying the compulsion against women with the compulsion of the Wehrmacht is tantamount to reversing the roles of victims and perpetrators. Moreover the perpetrator’s motives are irrelevant to the definition of forced prostitution. It remains unclear why it should be relevant that their own landsmen were involved in referring/selling women to the brothels when answering the question of whether or not violence against women of another country was committed. Furthermore unclear is why the author only speaks of instances of direct cimpulsion to begin with. Calling the proceedings of the Wehrmacht in the context of Wehrmacht brothels „Bemühungen“ (endeavours) is euphemistic. Apart from that, it remains unexamined why the Wehrmacht needed these brothels, and if they were truly a necessity; the questioning of a hypothetical indispensibility of prostitution in the society is missing.

[68]Cf. ibid, p. 169: „[…] bestand offensichtlich eine gewisse Auswahl. Eine ausrechende Zahl von Französinnen erklärte sich aus welchen Gründen auch immer bereit, in einer solchen Einrichtung zu arbeiten. […] was auf einen Überschuß an Prostituierten dort schließen lässt. Die teilweise hohe Fluktuation der Prostituierten in den einzelnen Bordellen des Festlands […] belegt ebenfalls eine relativ große Zahl verfügbarer Interessentinnen, auf die kein Zwang ausgeübt werden mußte. Gleichzeitig belegt schon allein der Umstand der hohen personellen Fluktuation, die die Deutschen ja wegen der damit verbundenen großen Ansteckungsgefahr eigentlich bekampften, daß von einem erzwungenen Verbleiben von Frauen an ihrem Arbeitsplatz, also von Zwangsprostitution, in der Praxis nicht gesprochen werden kann, so rigide einige Vorschriften auch theoretisch waren.“

([…] there was obviously a certain choice. A suficient number of French women were for whatever reason willing to work at such an establishment. […] which is indicative of an abundant number of prositutes there. The in part high fluctuation of prostitutes in their respective brothels on the mainland […] also proves that there was a relatively large number of interested women available, who did not have to be forced. At the same time, the circumstance that there was high fluctuation in personnel, which the German intended to work around due to high risk of infections, proves that one cannot see this as a de facto forced stay for these women at their place of work, i.e. forced prostitution, however rigid some of the regulations might have been in theory.)

The verbiage alone („erklärte sich bereit“ [to be willing], „Interessentin“ [interested woman], „aus welchen Gründen auch immer“ [for whatever reason]) facilitates the denial and marginalisation of violence against women. Fluctuation is no sign of voluntary prostitution. It is a tradition in the mileu to replace the women in the brothels to offer variety to the Johns. Plassau also fails to point out where this fluctuation was headed (to the next brothel? Away from prostitution? Insa Meinen has shown that the latter was not all that easily accomplished). Plassmann furthermore contradicts himself, when he claims that force was not a factor because there were enough prostitutes – right after he stated that the Wehrmacht did not have any other choice but to do as they did precisely for lack of „verfügbaren Interessentinnen“ (available interested women).

[69]Cf. ibid., p. 316 When occupants push women into prostitution and then extort a registration with a Wehrmacht brothel from them, it can hardly be considered a benefit on behalf of the women that the occupants take care of orderly („ordnungsgemäßen“) prostitution procedures and that they have an interest in keeping the women healthy (so they are able to exploit them further!). The „positive balance“ („positive Bilanz“) that Plassmann draws for the German side furthermore reveals an offenders‘ perspective.

[70]Ibid., p. 169: „Die Schließung nicht ökonomisch arbeitender Häuser deutet ebenfalls darau hin, da sie als Wirtschaftsbetriebe geführt wurden, die einen Gewinn erzielen sollten, nicht aber als reine Zwangsanstalten.“ (The liquidation of economically unprofitable houses, too, indicates that they were seen as economical enterprises that were supposed to make profits rather than plain compulsory institutions.) One may wonder what definition Plassman has for prostitution if he is capable of ignoring that, at its core, prostitution is the economisation of female bodies with whose sexual „management“ profits are made. What else is a brothel if not an economic establishment? And why should forced prostitution rule out that profits are made notwithstanding?

[71]Wendy Jo Gertjejanssen, whose work on sexualised violence at the eastern front during WW II also covers the brothels, comes to the conclusion that these brothels were a matter of sexualised violence. She is the only one who consistently denotes what happened at the brothels as rape, by which she takes a stand against an appalling trend of understanding prostitution as sex labour („Sexarbeit“) and forced prostitution as forced sex labour („Sexzwangsarbeit“) (For how is forced sexual intercourse different from rape, even if someone receives money for it?): Gertjejanssen, Victims, Heroes, Survivors.

[72]Eigendorf, Deutschland ist Umschlagplatz; Kittel, Deutschland ist ein Paradies.

[73]Forced prostitution has not been defined as an offense in Germany, neither scientifically, nor legally. The German criminal code lists an offense under §232 StGB, named „Menschenhandel zum Zweck der sexuellen Ausbeutung“ (human trafficking aimed at sexual extortion), that comes close, as it is in place to punish anyone who „recruits, transports, transfers, harbours or receives another person by taking advantage of that person’s personal or financial predicament or helplessness […] if that person is to be exploited by way of engaging in prostitution or performing sexual acts on or in the presence of the offender or a third person, or having sexual acts performed on them by the offender or a third person […]“ quoted after Prof. Dr. Michael Bohlander, Gesetze im Internet (online) <https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/englisch_stgb/englisch_stgb.html#p2086> last checked Feb. 13th 2021. [Correctio: § 232a is in place since October 15th 2016.]

[74]Cf. Mühlhäuser, Eroberungen, p. 223-5; cf Paul, Zwangsprostitution, p. 103-7; cf. Gertjejanssen, Victims, Heroes, Survivors, p. 179-186; cf. Beck, Wehrmacht und sexuelle Gewalt, p. 115 f.